Tuesday, 29 December 2009

Atlantic Solstice

Thursday, 17 December 2009

Northern Lights 3

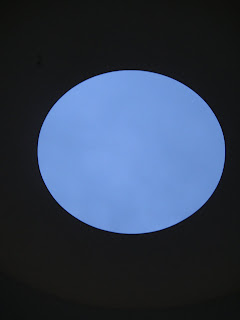

I had a proper go in his Sky Space at Kielder Water last month, a few days before the rains flooded Cumbria. It was alreayd pretty wet, and I'd driven for two hours in the rain from Durham. Kielder Forest feels very remote.

The lake has a lot of outdoor art on its shores, and three bothies nearby. It sits in a sweeping valley that looks great from the Sky Space. The skies are the clearest in England, hence the sharp timber of Kielder Observatory, a short walk from Turrell's piece.

I wandered up the mountainside from the observatory. Paths came and went, and I stumbled through bogs, tree stumps and peat hags to get a good view over the valley.

It was raining again as I got back to the Sky Space, so the shelter was welcome. I stayed as dusk fell and the sky darkened. The rain fell on the gravel below the aperture in the roof.

Turrell's talent is to get out of the way. The art is the viewer's experience, often of an interaction of light and architecture. The Sky Space is a different show every day.

http://www.visitkielder.com/site/things-to-do/art-and-architecture/art-and-architecture-list

http://www.mountainbothies.org.uk/

http://www.artfund.org/turrell/james_turrell.html

Tuesday, 24 November 2009

Northern Lights 2

One of the best elements of the event was 'Power Plant', a show in the Botanic Gardens produced by Simon Chatterton, centred on the work of the brilliant Mark Anderson, and originally commissioned by Oxford Contemporary Music. A succession of sound and light installations took you on a surreal journey through the darkened gardens.

The clear crowd-pleaser was Mark's 'Pyrophones' - a surround-sound fire organ. This is what it looked like in Liverpool last year:

Back in Durham's city centre, I was surprised to find that one of my favourite pieces was actually sited indoors, within the Cathedral. 'Chorus' by Mira Calix and United Visual Artists was a beautiful piece of music played through four static speakers and eight speaker/lights housed in pendulums that swayed and paused overhead, as the audience passed beneath them. I sat in a pew and watched the whole piece twice:

The North East can't be accused of not being ambitious in terms of large-scale outdoor arts events - next up is an illumination of the 87-mile Hadrian's Wall on 13 March 2010.

But for me the most poignant piece in Lumiere Durham was this simple light sculpture, produced from a drawing made by a prisoner at HMP Durham. How I take my freedoms for granted.

http://www.artichoke.uk.com/

Wednesday, 11 November 2009

Endangered Species

Of course it's all good fun, but it strikes me that there's a connection to be made. As the population of outdoor children plummets towards extinction, more and more adults emerge disconnected from the natural environment and find it harder to perceive the effects of climate change, pollution and species loss that ultimately threaten humanity. So my hypothesis is that a trend in the population of outdoor children could predict a trend in the population of homo sapiens.

Ultimately, re-connecting children with nature is not altruistic. There are billions of other planets, but my DNA is stuck on this one.

Wednesday, 4 November 2009

Northern Lights

Sunday, 4 October 2009

Bothy in the Black Mountains

After a brief but entertaining game of hide-and-seek, the bothy finally gave up its location at the bottom of a steep gorge where the stream flows into the dammed valley. It was fairly invisible from the path.

With the stove roaring, dinner on and the candles flickering, I put my sense of euphoria down to the night walk, the stunning location and perhaps partly the Sambucca. I kept having to go back outdoors to admire the fat silver moon gleaming over the reservoir and the bulk of the Black Mountains.

Thursday, 24 September 2009

Schools Without Walls

Picture a school. Do you see a building?

Schools can't bear the whole burden of reconnecting our children with the natural world, but they can certainly do their bit. The Forest Schools initiative is one the best vehicles we have for helping schools to move lessons outdoors: it is systematic, sustainable and easily understood.

After a period of accredited training that can be fitted around their existing job, a teacher takes pupils out into a local woodland for half a day every week or fortnight. There's huge diversity in the practice, but commonly the subjects of the 'normal' curriculum are taught through the use of natural resources, and there is an emphasis on social and emotional development. Over time, pupils learn to use tools, to control fire and to manage their environment responsibly.

Surprise surprise, children who spend regular time outdoors find it easier to concentrate, show fewer symptoms of ADHD, develop better social skills, improve their creativity and outperform their indoor peers in academic achievement.

Research in the US has led to calls for a daily 'green hour' for children, as a pre-condition for effective learning. It's a start, and I sense that a more fundamental change is coming.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forest_Schools

http://www.childrenandnature.org/

Thursday, 3 September 2009

In Search of Stone

There's an etymological relationship between art, artifice and the artificial, but my interest is the opposite: I see art as a natural aspect of our behaviour as a species, just as other animals have their inevitable forms of culture. What I enjoy most about Peter's work is how alive and organic it feels. Somehow he intersects animal, vegetable and mineral, to make sculptures that look like a living part of the landscape.

I loved Peter's sculptures at the Eden Project and Yorkshire Sculpture Park, and wanted to see more. After the pristine finish of the Eden commission, I was irrationally shocked to find his pieces in the Forest of Dean being colonised by mosses when I visited in 2008. Of course outdoor sculpture has to weather naturally, and the ageing of work is often intended by its maker, but initially I struggled with the contrast in presentation.

A year later and a year further on in my own outdoor arts career, I couldn't miss Peter's major exhibition at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (closes January 2010) and headed up the M1 earlier this summer.

It was fantastic to see so much of his work, but strangely unsatisfying to see it all in one place.

I guess I'd got used to the idea of searching for Peter's stones: making special journeys and enjoying the sense of discovery and the relationship between the work and its location. For me, Peter's work needed to occupy a more fertile space than it was given at YSP. And the continuous reminders of the 'no touching' rule hardly invited personal connection to the art. Of course I snuck a few touches while the stewards weren't looking: just to look is to miss half the point of sculpture.

The YSP experience reminded me how important environment is to my enjoyment of art, and made me want to re-experience Peter's work in a wilder context. The artist Jenny Kyle lives near Peter, and had told me before about a series of his sculptures installed around the Teign Valley in the early 90s by Common Ground. I got hold of a beautiful book about the project, 'Granite Song', with photos by Chris Chapman and some interesting essays. I learned that granite contains no fossils because it predates life on earth.

Armed with grid references and a few spare hours when passing through Devon this week, I set out to try to experience some more of Peter's art in a wilder and less formal context.

This piece, 'Passage', stands perfectly atop an avenue of old Beech trees across the valley from Castle Drogo, reached by an unmarked permissive path up the hill from the River Teign. The weathering of the stone has created the illusion of the lead inlay standing proud of the cut faces of the boulders. It appears to have stood there forever.

On an island in the River Teign downstream of Chagford sits 'Granite Song' itself, the first of the iconic split boulder forms that have become such a motif in Peter's work. It's exquisite - and in quiet counterpoint to its setting of woodland and rushing water. You'd miss it from the footpath if you weren't looking for it.

Perhaps it's special to me on its own account - it's pretty gorgeously curvy and pointy, and on a more intimate scale than many of the pieces carved after it. Or perhaps it's because I waded across a river and beheld it with all my senses that the joy of it still rings in my ears.

Tuesday, 25 August 2009

Happy Birthday Outdoor Culture

This means that Outdoor Culture is now officially a not-for-profit social enterprise - a status that properly reflects my aim to highlight the links between the health of our children, our environment and our society, and to forge fresh and meaningful connections between the arts, education and ecology sectors.

In practical terms, this is something of a rebirth for the company, as it confers extra credibility when meeting new partners and greater autonomy to access funding streams with less reliance on the charitable partners we work with. Outdoor Culture CIC can be bolder and more daring that its predecessor.

The mission remains the same: to create imaginative experiences beyond buildings, that explore human wildness and reflect our natural heritage.

I still can't quite call myself a social entrepreneur without wincing, though. It's a bit worthy and earnest, and wrongfully implies that I know something about business. I may stick with the arts label of creative producer for now ... unless social entrepreneurs get cheaper insurance?

Wednesday, 15 July 2009

Playing with Fire

.jpg)

Monday, 15 June 2009

Fun in the Sun

Not your average Lakeland weather.

Climbing the ridge up beyond the tree line.

Ennerdale Water, from near the summit of Haycock - the hills of Galloway just visible across the sea.